19 Aug 100 Years of Afghan History in Writing

Blog posts reflect the views of the authors and not those of AREU.

Our sense of self is grounded in our understanding of the past. Nearly 90 years ago, historian Carl Becker, in his presidential address for the American Historical Association titled “Everyman His Own Historian,†stated that history is “an unstable pattern of remembered things redesigned and newly colored to suit the convenience of those who make use of it.â€[1] Today, within the Afghan public sphere, history is redesigned and contested, told and re-told through diverse perspectives. The way in which we understand the past is not based on static and unchanging facts, but through a dialogue – reworked, criticized, challenged, and revised. These interpretations and re-interpretations of the Afghan past either challenge or add to the dominant historical narrative both locally and nationally.

The three textual bodies that have shaped the study of Afghan history are local texts mostly written in Persian; British-Indian and Russian colonial and diplomatic texts; and fieldnotes, books and articles written by anthropologists and folklorists (both Euro-American and Afghan).[2] As historians, we are trained to problematize and offer a contextual basis to this history writing, or historiography, as no work of history is complete or beyond criticism. We consider the factors that have shaped the recording of the past and in turn have shaped our interpretation of it. We constantly rewrite and reinterpret the past through diverse methods and reach new conclusions.

Official and institutional Afghan historians wrote history to encourage nationalism and legitimize the nation-building activities of the ruling establishment under heavy censorship. At the beginning of the 20th century, the court historian Fayz Muhammad Katib authored a history of 18th–and 19th–century Afghanistan, SirÄj al-TawÄrÄ«kh, a magisterial work published in three volumes. His work was subject to review and censorship under Amir Habibullah (r.1900-19), Amanullah Khan (r.1919-29), and Mahmud Tarzi until it was banned by Nadir Shah (r. 1929–33).[3] Under Nadir Shah, the Anjuman-e Adabi-ye Kabul (Kabul Literary Society) was established “to study and clarify Afghan historical heritage; to study and promote Afghan literature and folklore; to engender and promote the Pashto language; and to spread knowledge about Afghanistan and its culture.â€[4] Nadir Shah sought to promote history-writing to legitimize his regime and, as such, all publications were under strict state control.

In the 1960s, AfghÄnistÄn dar masÄ«r-e tÄrÄ«kh (Afghanistan in the Course of History) by the historian Ghulam Muhammad Ghubar provided a socialist history of Afghanistan. After its initial acceptance for publication by the Ministry of Information and Culture in 1967, its distribution was banned shortly afterwards.[5] Its copies, however, were widely read abroad and smuggled in Afghanistan to be secretly distributed.

Since the 1980s, after the weakening of the center during the Soviet-Afghan war, Afghan historiography has sought to “prove†or “disprove†official versions of Afghanistan’s national narrative in both its official and unofficial forms.[6] During the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) government, Afghans and members of the mujahideen narrated their own histories, mostly focused on their activities against the PDPA and the USSR in uncensored environments such as Iran and Pakistan. While Kabul promoted the communist regime’s campaigns of reform, these groups utilized print media to counter communist propaganda and express what they considered to be the most urgent, underreported issues regarding the Soviet-Afghan war.[7] The years of Soviet occupation generated historical literature among Afghans who fled the country and escaped the censorship of both the socialist government and the subsequent Taliban ruling.[8] This distance, as Tarzi states, afforded Afghans “the freedom to write about their country without the fear of persecution and use the medium of historiography to legitimize and broadcast their country’s national struggle or local, ethnic, or regional causes with a frequency and speed never experienced before.â€[9]

Since 2001, the framers of the modern state structure (the Afghan government, the United Nations, and the international community) have attempted to establish a national history for the sake of national unity.[10] This has entailed remaining selective of the past in our school textbooks, which do not discuss the Soviet-Afghan war, the devastation that Afghans witnessed after the Soviet invasion, the reign of the Taliban regime, or the recent presence of the U.S and NATO forces.[11] When prominent figures of the recent Afghan past are visible in our socio-political sphere and serve in formal state structures or hold meetings with the international community as our representatives, we are not equipped with the histories of their – and the nation’s past.

Today, we are able to speak and write about Afghanistan in a way that is critical towards nationalist ideology and not censored by our government. Healing and moving forward is not achieved through collective amnesia for the sake of national unity. We need to know where old grievances stem from, the mistakes our governments made, and the events that were formative in our country’s history. Only this way can we stand united with a common goal in the face of challenging decisions.

Munazza Ebtikar is a PhD Candidate in the University of Oxford and a member of the Royal Historical Society (RHS)

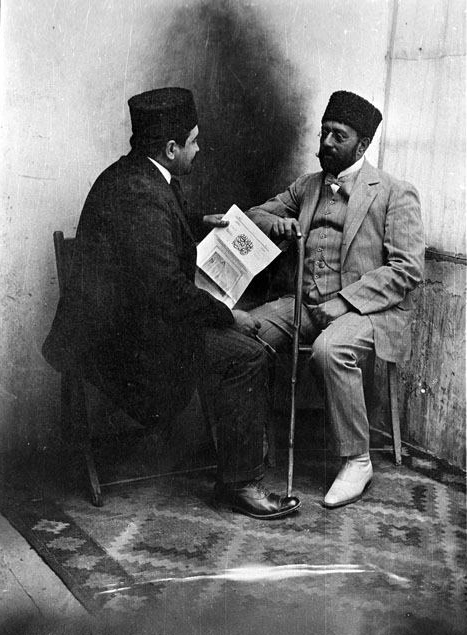

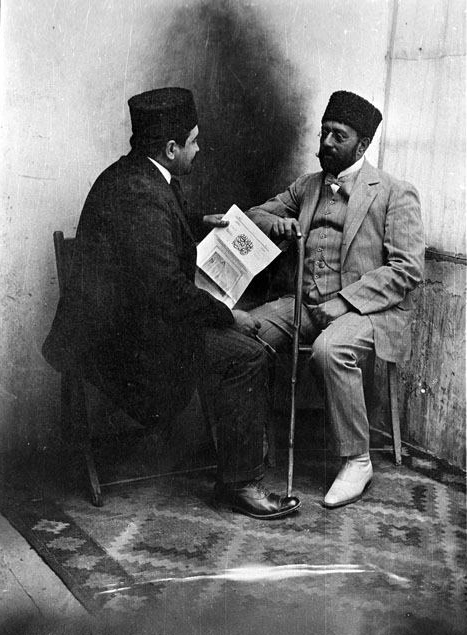

Photo: Mahmud Tarzi discussing the Persian bi-weekly periodical Seraj al-Akhbar (The Torch of News), which helped launched the development of the Afghan press.Â

[1] Becker, Carl. “Everyman His Own Historianâ€. The American Historical Review, Volume 37, Issue 2, January 1932, pp. 221–236.

[2] McChesney, R. D. “Recent Work on the History of Afghanistan.†Journal of Persianate Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. 58–91, pg. 59.

[3] McChesney, Robert D. “‘The Bottomless Inkwell.’†Afghan History Through Afghan Eyes, May 2016, pp. 97–130, pg. 99.

[4] Gregorian, Vartan. The Emergence of Modern Afghanistan: Policies of Reform and Modernization, 1880–1946, Stanford University Press, 1969, pg. 348.

[5]Nawid, Senzil. “Writing National History: Afghan Historiography in the Twentieth Century.†Afghan History Through Afghan Eyes, Oxford University Press, 2016, pg. 203

[6] Tarzi, Amin. “The Maturation of Afghan Historiography.†International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 45, no. 01, 2013, pp. 129–131, pg. 129.

[7] O’Sullivan, Piper E. “Literary Politics of the Soviet-Afghan War.†Indiana University, 2018.

[8] Green, Nile. “A History of Afghan Historiography.†Afghan History Through Afghan Eyes, Oxford University Press, 2016.

[9] Tarzi, Amin. “The Maturation of Afghan Historiography.†International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 45, no. 01, 2013, pp. 129–131, pg. 129.

[10] “Afghanistan National Development Strategy 1387–1391 (2008–2013)â€. Afghanistan National Development Strategy Secretariat, Kabul, 2008, pg. 11.

[11] Bezhan, Frud. “New Afghan Textbooks Sidestep History.†RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, 20 Feb. 2012.